Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution grants the President the power to “grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.”

The Supreme Court interprets this language to include the power to grant pardons (full and conditional), commutations of sentence, conditional commutations of sentence, amnesties (or group pardons), remissions of fines and forfeitures as well as reprieves (or respites).

The most common grants have been individual pardons (which simply restore civil rights) and commutations of sentences (which reduce the severity of a sentence).

Until the 1950s, presidents granted them every month of the term, or skipped one or two months at most. Consequently, there have been over 30,000 individual grants of federal executive clemency.

Demand for clemency was greater before the construction of large federal prisons in the late 1800s.

Federal prisoners were initially housed in state and local facilities at considerable inconvenience and great cost.

Thus, with the advent of the federal prison complex (Leavenworth, Atlanta and McNeil Island), and the creation of alternative release mechanisms (federal probation and parole), the significance of clemency was reduced considerably.

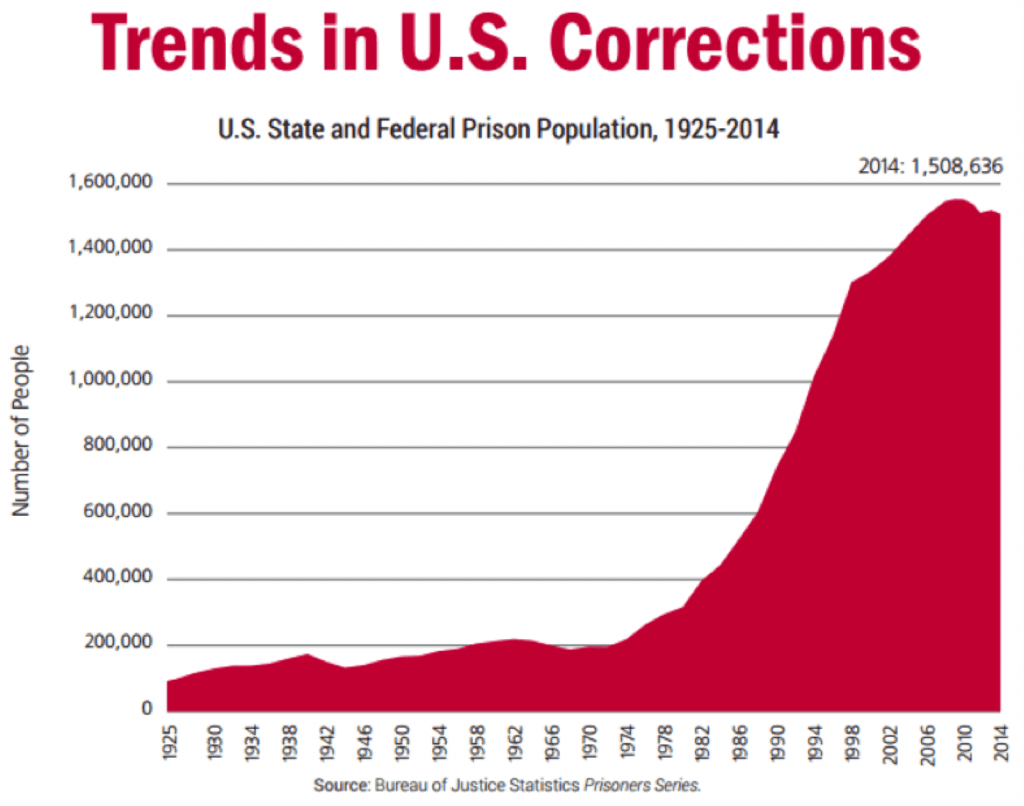

Increasing federalization of criminal law then played a large part in a skyrocketing federal prison population.

Indeed, convictions under the Mann (White Slave) Act (1910), Harrison Narcotics Act (1914), Volstead Act (1918) and the Dyer Act (1919) prompted several more rounds of construction projects and creation of a Bureau of Prisons.

Similarly, legislation enacted subsequent to the so-called “War on Drugs” (1980s) and use of mandatory minimum sentences resulted in steady, dramatic increases in the federal prison population – currently around 200,000, a 700 percent increase from 1980.

As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama expressed interest in reforming our criminal justice system. He specifically condemned America’s high incarceration rate, unduly harsh mandatory minimum sentences and disparities in sentencing based on race.

He was also critical of the 100 to 1 sentencing ratio scheme for crimes related to crack v. powder cocaine (individuals caught with 1 gram of crack cocaine were sentenced in the same manner as individuals caught with 100 grams of powder cocaine).

Furthermore, in a Town Hall meeting, Obama said part of his personal faith was belief “in the idea of redemption, that people can get a second chance, that people can change.”

Statements like these encouraged many to believe that, as president, Obama would make greater use of the pardon power.

Hope, however, was met with crushing disappointment. Obama waited 682 days before granting the first pardon of his presidency (the second longest delay ever). His first term featured 22 pardons and just 1 commutation – the lowest level of clemency activity for a full term since George Washington’s first.

On the other hand, in August of 2010, the President signed the Fair Sentencing Act which reduced the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentencing, from 100 to 1 to 18 to 1. The Act also eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack.

The immediate question was: what would happen to the thousands of persons sentenced under the old guidelines, especially since Congress showed no willingness to apply the Act retroactively?

In January of 2014, Deputy Attorney General David Cole announced a Department of Justice initiative, Clemency Project 2014, which called upon a collection of private practice lawyers to collect and submit applications for commutations of sentence.

Cole noted there were many “low-level, nonviolent drug offenders” in prison “who would likely have received a substantially lower sentence if convicted of precisely the same offenses today.” He added this was “not fair, and it harms our criminal justice system.”

At the time, the Justice Department was already receiving record numbers of commutation applications, but the Project aimed to identify applicants who had no significant criminal history, were low-level non-violent offenders and had served a considerable portion of their sentence.

In addition, a record of good conduct was preferred. Thousands of applications flowed in, but only a single commutation was granted over the next 11 months.

Finally, in December of 2014, the President granted 23 commutations of sentence. In 2015, 165 commutations followed.

So far, in 2016, he has granted 493. Consequently, the President’s current total for commutations (673 – almost all for drug offenders) is greater than that of several of his predecessors combined and more than any single president has granted since Calvin Coolidge. More than 240 of the sentences that have been commuted were for “life.” Another 130 have involved sentences of 25 years or more.

President Obama clearly came into office with more political capital to spend on clemency than any president in a half a century.

Public opinion on drugs has changed considerably in recent years and the momentum toward legalization of marijuana is significant. Increasingly, the political left and right agree our law is over-criminalized, that prisons are expensive and that imprisonment may not be the most effective way to deal with many offenders.

To be sure, the President and his supporters can proudly point to his prolific use of commutations. But aggregate data does not tell the whole story.

As noted, the President was slow to use the pardon power and the first term was notably merciless. In addition, most of the President’s clemency activity has come in the last year of his second term.

Indeed, by the time his administration ends, Obama will have probably produced the most significant last-minute clemency surge in history. So, unfortunately, mercy appears to have been a low priority, an afterthought.

Finally, there is little evidence that the President has done anything to reform the administration of the clemency power long-term. To those who have argued that the handling of applications needs to be removed from the hands of career prosecutors in the basement of the Department of Justice, this administration has left a lot to be desired.

To read more about human rights, be sure to check out our cluster page by clicking on the link below.

This article was previously published on the Learn Liberty blog.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions.