Since 1996, the Pentagon has lost track of $8.5 trillion — it simply doesn’t know what the money was spent on. That doesn’t even include the billions lost to known waste and abuse. But despite that troubled budgetary record, the US government post-Obama increased defense spending by billions.

The U.S. House of Representatives passed the defense spending bill for fiscal year (FY) 2017, which provided $516.1 billion in the “base budget” and $61.8 billion for “Overseas Contingency Operations” — i.e., wars. This represented an increase of $5.2 billion over the previous fiscal year.

Adding the $5.8 billion in supplemental funding provided by December’s continuing resolution and various other factors, the budget came to a total of $646.75 billion for the year.

Though some members of the House hailed the new bill as a pivot from defense spending cuts and a necessary step toward increasing national security, it is useful to put this budget in context. Military spending peaked in FY 2011, and the reduction since has come out of money spent on the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, rather than from the Pentagon’s base budget.

The base military budget keeps increasing even without war

Despite the sequestration in 2013, the base budget continued to rise once again, and though the active military engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan cooled off, continued military action there and elsewhere kept the OCO account open.

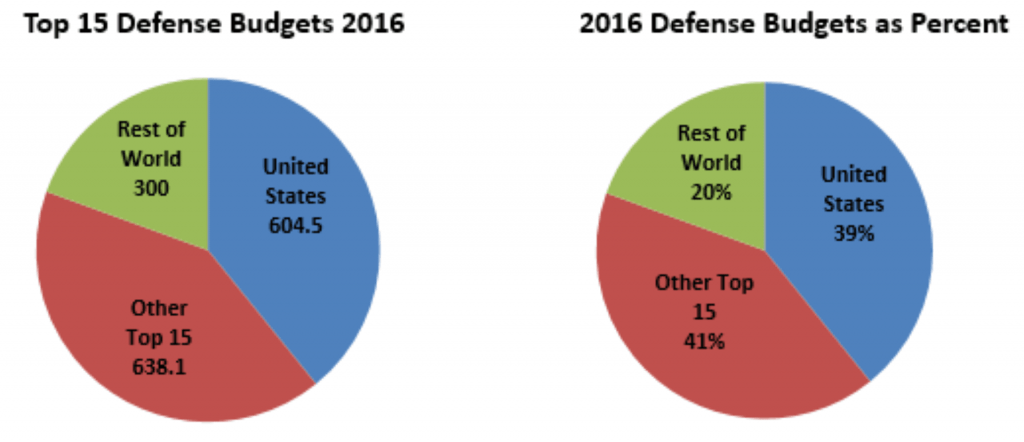

The International Institute for Strategic Studies provides detailed calculations of total world defense spending that shed light on how the United States compares to the rest of the world. By the Institute’s calculations, the United States in 2016 spent 39 percent of total world defense spending, only 2 percent less than the next 15 countries — including China (10 percent) and Russia (4 percent) — combined.

Source: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2017

Those percentages are a function of other nations’ spending decisions, as well as those of the United States. You might think that if security was the main driver of defense spending, spending as much as the next 15 nations combined should be more than enough to provide a reasonably secure environment. An increase in spending for 2017 may seem excessive.

The aforementioned House bill contained $6.8 billion more in additional procurement funding than even the original 2017 request from the Obama administration. It included “$750 million for six additional Navy and Marine Corps F-35 Joint Strike Fighters and $495 million for five extra Air Force F-35s,” as well as “$433 million for the DDG-51 destroyer program, a third Littoral Combat Ship and $150 million in advance procurement for a new polar icebreaker.”

Both the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and the Littoral Combat Ship are produced by Lockheed Martin, and both have been plagued by cost overruns and technical problems. Yet even with the overruns and the verbal sparring over the dysfunctional budgets, the bill still increased spending for these projects.

Lest you think that Lockheed Martin is alone, it should be noted that these are only two programs in a general pattern of behavior within the defense sector.

The military has no incentive to be efficient and save money

Consider the $31 to $60 billion lost due to waste in Iraq and Afghanistan, or the potential misuse of the OCO “slush fund” since the conclusion of those wars. Or even the known cases of waste and abuse, such as spending $1 billion to destroy $16 billion in ammunition, or $1 billion for shoddy airplane maintenance. Let alone that missing $8.5 trillion…

How does such behavior persist in the defense sector, and even seem to be rewarded with additional spending? The answer is straightforward: it may be that military spending, rather than being purely about security, has a political component as well.

The political nature of defense spending comes about in two interrelated ways.

First, the nature of the budgetary process, financed through a system of generalized taxation, erodes the link between decision-making and those who bear the full cost of the decision. In fact, rather than being faced with the full cost of decisions, agencies in the defense sector face a perverse incentive. When a private firm makes budget errors, it risks losing shareholder value.

However, if a defense agency does not spend its entire budget, that money will be cut and given to someone else. Rather than being punished for overspending, agencies are punished for saving money. The Department of Defense does not have shareholders, and there is no real recourse for taxpayers to sanction egregious misuse of resources.

The political process gives billions to well connected people

Second, defense spending decisions are made through a political process that requires agreements between the Pentagon, the President, and Congress. Firms that want to succeed in this process need someone politically connected and skilled at navigating the system on their payroll, and they need to use those skilled and connected people in lobbying to keep the defense budgets high.

2017’s budget cycle was no different. To see how this works, let’s return to Lockheed’s troubled F-35 program. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, in 2016, “70 representatives signed a letter to the leadership of the House Defense Appropriations subcommittee urging continued support for the program. In the 2016 cycle, those 70 lawmakers received nearly $3.5 million from the defense sector” and “collectively received a total of almost $578,000 from Lockheed Martin in the 2016 cycle, nearly 17 percent of their defense dollars.”

It does not take much imagination to envision a relationship between campaign contributions, letters, and increases in spending for the program. Again, Lockheed is not the only player in this game. It is simply one illustration of the phenomenon.

It is not difficult to see why these dynamics in national defense create what is sometimes referred to as the “permanent war economy.”

While it may not be possible to completely remove politics from such decisions, these dynamics should not go unnoticed when the U.S. taxpayer and voter are offered the rationale of national strength and security as the primary reason for increased spending. That rationale is not the only incentive that policymakers face when engaging in public sector budget decisions.

To read more about the costs of war, be sure to check out our cluster page by clicking on the button below.

This article was previously published on the Learn Liberty blog.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions.